This is the Weight and Healthcare newsletter. This is the first part of a two-part exploration of this topic. To make sure that you don’t miss part two, you can subscribe here! You can also gift a subscription to a friend, family member, even a healthcare practitioner!

A frequent claim made by those who push a weight-loss-for health-paradigm is that “losing just 5-10% of your body weight produces clinically meaningful health benefits”

It’s been repeated so often that people assume that it is based in research and science. But where did this idea come from? And is it really supported by the evidence.

Let’s take a look.

First, I think it’s telling that a lot of weight loss research doesn’t include health metrics at all. They simply make vague (and typically uncited) claims about how weight loss improves health, and then just assume that being thinner will make subjects healthier (often despite the fact that subjects are engaging in behaviors that would be considered unhealthy in a thinner person, but that’s a subject for another day.)

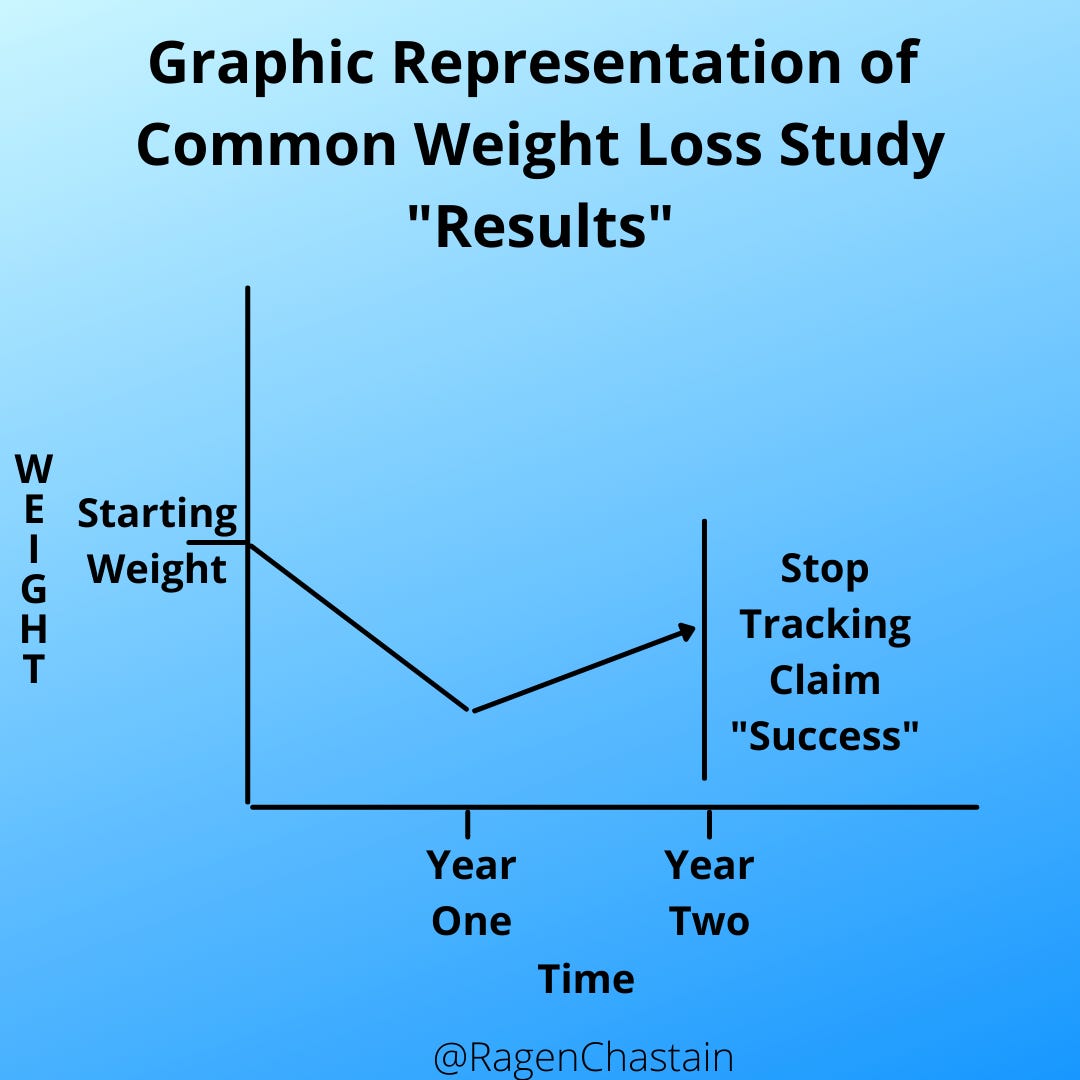

Also, as we’ve talked about before here, long-term research shows that almost everyone loses weight short-term but gains it back within 2-5 years. Many weight loss studies skirt this issue by tracking subjects for a maximum of two years (and often far less.) In the two- year studies, we often see conclusions such as “subjects lost 10 pounds in the first year, gained back 5 pounds by year two, but remained below their original weight.”

As a reminder, if a trajectory is clearly going straight up, good research methods do not allow us to simply stop tracking and lead people to believe that the results leveled off right there. So what many studies of weight loss do is baselessly claim that weight loss will improve health, and then claim that their intervention produced weight loss by ending the study before all of the weight is regained. In graph form, it looks a bit like this for 2-year studies:

So let’s talk about this 5-10% weight loss idea.

The first thing to understand is that this number was arrived at not through research, but through attrition.

Originally, the idea of a “healthy weight” was based on the Metropolitan Life Insurance Tables which gave specific weight ranges based on height and frame.

But fat people almost never lost enough weight to hit these goals, so they moved the target to 20% of starting body weight. Again, not because research showed that a 20% loss produced health benefits, but because it seemed like a more achievable goal.

Except it turns out it wasn’t a more achievable goal. As Tomiyama, Ahlstrom, and Mann put it in their 2013 paper

“only 5% of ob*se* dieters succeeded by that definition (Stunkard & McLaren-Hume 1959) Over the next 30 years, reviews of diet studies showed that individuals tended to lose an average of about 8% of their starting weight on most diets. In an effort to create a move achievable goal, but without any particular medical reason, researchers lowered the standard to just 5%. [emphasis added]

So, for the record here is the amount of weight doctors would have told me that I, personally, needed lose in order to get health benefits:

1942: At least 150 pounds

1959: 57.6 pounds

1995-present: 14.4 pounds

To be clear, there is nothing wrong with changing healthcare recommendations based on evidence (that is, in fact, what we are seeking to do by instituting weight-neutral healthcare) But remember – the only “evidence” these changes were based on showed that people rarely succeed at weight loss. These changes are not about creating health, they are about moving the goalpost on “successful” weight loss and declaring victory.

To put the icing on this preposterous cake, even though losing 14.4 pounds would not even come close to changing my BMI category (it wouldn’t even come close to changing my “class” of “ob*sity”) the same healthcare practitioners who are peddling this “5-10%” number are often still also peddling BMI as a helpful tool (rather than the racism-based*, patient-harming, diet-industry-profit- generator that it actually is.)

Back to Tomiyama, Ahlstrom, and Mann. Their paper looked at 21 diet papers that had weight loss as a goal of the intervention, were randomized controlled trials and included a non-diet control group, and included at least two years of follow up. They looked at health outcomes including cholesterol, triglycerides, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, and fasting blood glucose, as well as examining whether the amount of weight that was lost predicted the health outcomes

What did they find?

“Across all studies, there were minimal improvements in these health outcomes and none of these correlated with weight change”

They did find that there were “a few larger positive effects” related to hypertension and diabetes medication use and diabetes and stroke incidence. But they point out that

“In correlational analyses, however, we uncovered no clear relationship between weight loss and health outcomes related to hypertension, diabetes or cholesterol, calling into question whether weight change per se had any causal role in the few effects of the diets. Increased exercise, healthier eating, engagement with the health care system, and social support may have played a role instead.”

So what we typically see with dieting is that people make behavior changes. After those changes are made, those folks often see health improvements, and sometimes see a small amount of weight loss (at least in the short-term.) Even though the weight loss is small, and often largely simultaneous with the health improvements, the weight loss gets credited for the health changes, rather than seeing both the health changes and the (at least short-term) small amount of weight loss as resulting from the behavior changes.

Giving the credit to weight loss, rather than the initial behavior change, drives a lot of profit to the weight loss industry, but drives a lot of harm to fat patients. In part two of this two-part series, we’ll look at the ways that this harm plays out, and how the research not only doesn’t support crediting weight loss with health benefits but, in fact, refutes it.

If you want to take a look at the true ridiculousness of this using real numbers, you can find that here!

Did you find this post helpful? You can subscribe for free to get future posts delivered direct to your inbox, or choose a paid subscription to support the newsletter and get special benefits! Click the Subscribe button for details:

More Research

For a full bank of research, check out https://haeshealthsheets.com/resources/

*Note on language: I use “fat” as a neutral descriptor as used by the fat activist community, I use “ob*se” and “overw*ight” to acknowledge that these are terms that were created to medicalize and pathologize fat bodies, with roots in racism and specifically anti-Blackness. Please read Sabrina Strings: Fearing the Black Body – the Racial Origins of Fat Phobia and Da’Shaun Harrisons Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness for more on this.

Nancy, your assertion that you can just reduce the amount of food you eat, and move your body without a gym membership and lose weight is true, to some degree. The problem with that thought process is that I think you’re assuming that the weight is going to stay off. But once your body perceives that sufficient fuel is not available when it asks for it (and no, body fat, is not sufficient fuel) your endocrine system is going to change, metabolism, dropping by as much as nearly 20%, hunger hormones, increasing, satiety hormones decreasing, and with in 2 to 5 years you will have a 98% chance of having regained at least the amount of weight you lost in the diet and a more than 60% chance of gaining back more than you lost in the first place. So the important point is not that you can lose weight without paying WW or a gym, it’s that weight loss efforts don’t work in the first place.

The good news is that being in a large body has not been proven to be, in and of itself, unhealthy, and that if you have health problems that are correlated with your higher weight, that does not mean that the higher weight caused the health problem. Sometimes the thing that’s causing the higher weight is also causing the health problem. Being angry at gyms and weight loss programs is almost correct, if only you were angry with them for the right reason.

It’s hard. I’ve been body positive and health at every size for 6 years and I still get triggered, finding myself wishing my body was smaller. We live in a culture that says larger bodied people are irrelevant and so much worse. But I love my body, and I will not again starve it into (temporary) conformity to an ideal created by the avaricious weight cycling industry and a body-bigotry infested medical industry, willing to harm and even kill us for their profits. We are making progress and the adversary is fighting back, hard. Best to all of us in navigating this morass. Rebecca