It’s day 3 of launch week for the Weight and Healthcare newsletter and today we’re studying the studies with Gaesser and Angadi. If you like what you are reading, please consider subscribing and/or sharing!

In September of this year, Glenn Gaesser and Siddhartha Angadi published their paper “Ob*sity* treatment: Weight loss versus increasing fitness and physical activity for reducing health risks”

After reading through it, I knew immediately that it was a paper I would be referring to often. It is a view into the evidence for best supporting the health of higher weight people - an incredibly thorough look at the benefits of physical activity vs intentional weight loss. It cites 225 other papers, analyses, and meta-analyses.

Before we get too far into this, while physical activity is one option for weight-neutral health-promoting behavior, there are many other options for weight neutral care that aren’t explored here (including things like sleep, and stress management) It’s also important that public health focuses on things like removing barriers to access and improving social determinants of health (including ending oppression) rather than fixating on the choices of individuals, or trying to make the individual’s choices the public’s business.

Fitness is also not an appropriate intervention for all people, and often fat* people experience trauma around physical activity due to weight stigma that negatively impacts their relationship with fitness. And regardless of the possible health benefits, participation in fitness is never an obligation or barometer of worthiness.

Topline Findings

The mortality risk associated with ob*sity is largely attenuated or eliminated by moderate-to-high levels of cardiorespiratory fitness (CRF) or physical activity (PA)

most cardiometabolic risk markers associated with ob*sity can be improved with exercise training independent of weight loss and by a magnitude similar to that observed with weight-loss programs

increases in CRF or PA are consistently associated with greater reductions in mortality risk than is intentional weight loss

weight cycling is associated with numerous adverse health outcomes including increased mortality

I would summarize it in this way:

People with similar fitness habits have similar mortality risk regardless of size, and health can be improved through movement without weight loss. Increasing physical fitness is more health promoting than intentional weight loss attempts, which also carry with them the risk of weight cycling (or yo-yo dieting) which can negatively impact health.

So overall, fitness improves health as much or more than weight loss attempts without the downside risk of weight cycling (which is the most common outcome of intentional weight loss attempts.) and thus physical fitness is a much more evidence-based way to support health than weight loss attempts.

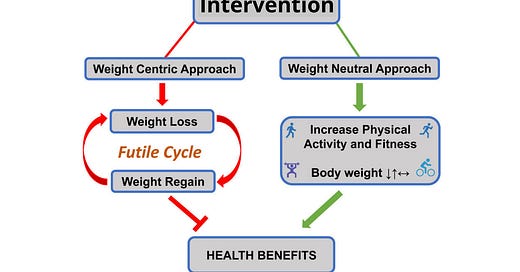

This image that they included is a thing of absolutely beauty, though I disagree with the idea of “ob*sity treatment,” but we’ll get to that in a moment.

Some Highlights

This paper is chock full o’ goodness, here are just some of the highlights:

Importantly, overw*ight and ob*sity in conjunction with moderate-to-high CRF (fit) were associated with a lower death rate than adults in the unfit normal-weight category

And

CRF does not eliminate the CVD mortality risk associated with high BMI. Nonetheless, the data illustrate that low CRF is more hazardous than is high BMI. In fact, the data in Figure 2 clearly show that risks associated with higher BMI within both unfit and fit groups are much lower than the risks associated with low CRF regardless of BMI.

and

Data on 21,925 men in the Aerobic Center Longitudinal Study demonstrated that lower all-cause and cancer mortality risks associated with higher levels of muscular fitness were independent of BMI, waist circumference, and percent body fat, and that the lower risk was observed even after adjusting for CRF

This is a good reminder of one of the many issues with pathologizing body size. It does a double disservice by suggesting to fat people (and their friends, family, and healthcare practitioners) that the only way for them to support their health is to attempt to become thin. It suggests to thin people that their body size is proof of their health. Both these statements are wrong, and harm often comes from their application, though the most harm is done to those at higher weights and/or those with multiple marginalized identities.

Overall, data from observational studies and RCTs do not consistently show that intentional weight loss is associated with reduced mortality risk. Even in those studies that demonstrated a benefit of weight loss, it is not clear whether the weight loss itself was the primary factor that reduced the mortality risk. This is because the RCTs included in the weight loss meta-analyses invariably incorporated changes in diet and/or exercise, either as a program that participants could attend or as advice. As discussed in subsequent sections, increases in PA are consistently associated with reductions in mortality risk independently of changes in weight.

This is something that has long frustrated me about discussions of weight loss and health. What typically happens with these weight loss attempts is that people make behavior changes, and then they experience health changes and a little bit of weight loss (at least temporarily.) Those who sell weight loss insist that even though the amount of weight lost is small, and even though it happens simultaneously with the health changes - the weight loss should be credited with the health impacts (rather than the behavior changes that preceded them both.)

I feel like you can only get to that conclusion by jumping off the logic train before it reaches the station.

A Closer Look

There are a few statements and conclusions that I want to look at more deeply:

Based on these findings, they “propose a weight-neutral strategy for ob*sity treatment

I absolutely agree with them on the weight-neutral strategy, but I would challenge the notion of “ob*sity treatment.” I think that accepts the (erroneous) premise that body size (as defined here by BMI) is, in and of itself, a pathology to be treated. In truth, these weight neutral strategies are applicable to people of all sizes. If fat bodies hadn’t been pathologized in the first place, we could just be talking about health promoting behaviors for everyone. (It would also have theoretically eliminated weight stigma and its harmful effects, but that’s a subject for another day.) I also want to point out that it’s very possible that the authors also don’t agree with the “ob*sity treatment” paradigm, but that it’s the paradigm they are working and writing and trying to get published in.

They also explain:

It is important to note that physically active adults in the normal weight BMI range had the lowest risk (0.22, 95% confidence interval 0.16-0.29), indicating that both PA and BMI contribute to CVD risk

I think it’s important to clarify that we don’t know if the actual BMI is contributing to the risk, or if it’s the things that people of higher BMI tend to experience more than those of “normal weight” including weight stigma, weight cycling, and healthcare inequalities, all of which have been shown in various research (some of it cited here) to increase CVD risk. They make this point later in the paper, but I feel like this statement can be misinterpreted so I wanted to point it out.

A weight-neutral approach does not mean that weight loss should be categorically discouraged. Such an approach may not be feasible when so many adults want to lose weight.

Many adults want to be able to fly. But if they go to their doctor and ask for a physical to be cleared to jump off their roof and flap their arms aggressively (even if they make a convincing argument that it will solve their joint pain if it works,) it is their doctor’s responsibility to inform them that it’s highly unlikely to work and that it will most likely cause harm.

I wish that whenever someone considered making statements like this, they would instead point to the need for a massive public health education campaign around the futility – and likely harm – of intentional weight loss attempts. I want a world where people know better than to ask for weight loss, and where you don’t have to become thinner to escape weight-based oppression. A good intermediary step would be a world where people who have been convinced by weight loss industry marketing (and the weight stigma it perpetuates) to want something that is harmful to them, are not simply acquiesced to by healthcare professionals who should know better.

I’m grateful to Gaesser and Angadi for their work, and I encourage you to read the full paper and please feel free to email me at ragen@sizedforsuccess.com if you have any questions/thoughts about this that you would like me to write about.

This is far from the only study that shows that weight neutral interventions provide far greater benefit with far less risk. You can check out the research list here for more information!

Did you find this post helpful? You can subscribe for free to get future posts delivered direct to your inbox, or choose a paid subscription to support the newsletter and get special benefits! Click the Subscribe button below for details:

More research and resources:

https://haeshealthsheets.com/resources/

*Note on language: I use “fat” as a neutral descriptor as used by the fat activist community, I use “ob*se” and “overw*ight” to acknowledge that these are terms that were created to medicalize and pathologize fat bodies, with roots in racism and specifically anti-Blackness. Please read Sabrina Strings: Fearing the Black Body – the Racial Origins of Fat Phobia and Da’Shaun Harrisons Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness for more on this.

Would you be willing to discuss a condition I was recently diagnosed with called "o*esity hypoventilation syndrome"? My pulmonologist tried to refer me to an "o*esity specialist" and I shut that down immediately.

I'm having severe shortness of breath upon even mild exertion (but only exertion) and likely have sleep apnea as well. She basically explained to me, using her hands and arms to illustrate, how having extra abdominal adipose tissue makes it difficult for the diaphragm to function as it should. The "solution" is IWL but I'm not convinced that works and would rather focus on healthy, sustainable habits instead, like increasing my activity level.

It's so freakin' hard to deal with doctors as a fat person and I didn't have the spoons to challenge her.