This is the Weight and Healthcare newsletter. If you like what you are reading, please consider subscribing and/or sharing!

I got the following question from reader Lynn:

“I know that they use BMI for kids and I know that it’s different than what they do for adults, but I don’t understand how. Maybe you could write a newsletter about it?”

Indeed I can Lynn, thanks for the suggestion! This gets a bit complex, so it’s going to be a two-part series. In part 1 we’ll look at the basics.

Also, I consulted with Deb Burgard, PhD, FAED who is a psychologist in private practice and fierce fat activist who has been a friend and mentor to me in many ways, including understanding this research and I’m so grateful for her help.

I also want to say a quick thanks to my paid subscribers. Now, whether you are a paid subscriber, free subscriber, or you just stumbled onto this piece I’m super happy that you are here! That said, this piece took many hours of research, and the support of paid subscribers allows me to take that time, so thanks a bunch!

Let’s start with Body Mass Index (BMI) in adults. BMI is a problematic, I would argue fairly useless, measurement and I wrote about that in detail here. BMI is just a ratio of weight and height - Weight in kg divided by height in meters squared (or in imperial measurements: weight in pounds times 703 divided by height in inches squared.) That equation determines adult BMI. It’s problematic, but it’s easy to calculate and clear.

Again, that’s in adults.

BMI for kids isn’t measured by just an individual equation. Instead, it’s measured by comparing kids’ height and weight ratio to percentiles derived from other kids of the same age and sex (currently only “male” and “female” are used with no inclusion of trans or nonbinary kids.) Currently the claim is that kids in the 85th percentile are “overw*ight” and those in the 95% percentile are “ob*se” which is a fairly new development, but we’ll get to that.

Let’s start with how the comparator percentiles were derived.

The charts that are used to judge BMI for kids are generated by the CDC and are called “Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Growth Charts: United States.” These charts were created in 2000 (to update the National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) growth charts that had been in use since 1977.)

You can find the full methods of development here (with a content note that they contain weight stigma, including stigmatizing terms.) They are 203 pages long, I read them all so you don’t have to (unless you want to, of course!)

There are a set of charts for birth to 36 months of age that include “sex-specific smoothed percentile curves” for

· Weight for age

· Recumbent length for age

· Head circumference for age

· weight for recumbent length

There are weight-for-stature charts for 77 to 121 cm which are “primarily intended for use among children from ages 2 to 5 years.”

There are charts for ages 2 through 20 that include:

· weight-for-age

· stature-for-age

· body mass index (BMI)-for-age curves

We are going to focus on the BMI-for-age curves because, upon announcing the charts, the CDC claimed that “the BMI-for-age charts represent a new tool that can be used by health care providers for the early identification of children who are at risk for becoming overw*ight at older ages.”

The Growth Chart data were pulled from “five crosssectional, nationally representative health examination surveys”

NHES II (1963–65) https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhes2/default.aspx

NHES III (1966–70) https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhes3/default.aspx

NHANES I (1971–74) https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes1/default.aspx

NHANES II (1976–80) https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhes2/default.aspx

NHANES III (1988–94) https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes3/default.aspx

Just to make sure it’s clear, the determination of whether kids today are at a “correct” BMI is based on how they compare to other kids from 1963 to 1994. So, the oldest data is 61 years old and the most recent is still 30 years old - except it’s not. The exclusion section of the CDC Methodology states:

“data from NHANES III for children greater than or equal to 6 years of age were excluded from the charts for weight-for-age, weight-for stature, and BMI-for-age. Inclusion of these data would have led to the underclassification of overw*ight, because overw*ight cutoff criteria based on weight- and BMI-for-age percentiles would have been shifted upward.”

I read this repeatedly and asked four different people about it to make sure that I understood this correctly, and I did. Here’s what happened: The actual data they had intended to include would have shifted the percentiles, placing kids with higher BMIs into lower

percentiles. Said another way, if they used all the data they intended to, fewer kids would be in the 85th percentile and above, and thus flagged as “at risk for overw*sight.” So, instead of increasing the criteria for being “at risk of overw*ight” based on the actual data, the group working on this chose to treat the kids from the NHANES III, who were unexpectedly heavier and/or taller, as outliers and omit the the most recent data (1988-1994) to keep the threshold for what would be considered “at risk for overw*ight” lower. To reiterate, they started with five data sources for ages 2-20, but excluded one of those data source, or 20% of the total data, for those ages 6-20 setting the threshold for “overw*ight” lower than it would be if the actual data were included.

That wasn’t the end of the statistical treatment, though.

They created percentiles based on the data they chose to include, then utilized a statistical technique called locally weighted regression or LWR (a process that, instead of looking at the totality of the data to create a curve, chooses specific data points and creates estimates for those points based on the values closest to those points) as well as data smoothing (which is a process of removing outlier data to bring patterns into sharper relief.)

Using this data and these techniques they created ten percentiles, explaining:

“Ten empirical percentiles were calculated for the BMI-for-age charts because the additional 85th percentile was required for boys and girls to identify children and adolescents at risk for overw*ight.”

What this means is that the previous charts included 5th, 10th, 25th, 50th, 75th, 90th, and 95th percentiles. The CDC added the 85th percentile as a way for, as they later explain in the methodology, “enhancing their use as screening tools to identify children and adolescents who may be overw*ight or at risk of overw*ight.”

Remember that the terms here were “may be…” and “at risk of…”. That’s going to come up again soon.

I want to be clear that when creating growth charts like this, there will always be kids in the higher and lower percentiles because that is the way that percentiles work, and that doesn’t mean that all of those in the higher and lower percentiles should be diagnosed with a health issue. For example, we would see this if we used height alone - there are always going to be taller and shorter kids. That doesn’t mean that every kid in the 85th percentile and above should be labeled “medically overtall.”

Importantly, at the time they were being created, these charts were not used for “diagnosis” of “overw*ght” or “ob*se” children but, rather, were used to look at general trends. Physicians were already looking for children who were on the lower end of the growth chart to make sure that there wasn’t something going on. The idea here was that they would also make sure there wasn’t something going on with kids in the higher percentiles. While I have concerns about that idea, it’s important that it’s not the same thing as diagnosing them as having the wrong size body and suggesting treatment for body size manipulation.

As a quick aside, one question I’ve always had about this data is around hunger. For example, was there greater hunger/food insecurity in the older data and was the jump in body size seen in the NHANES III possibly from weight restoration due to a reduction in hunger/food insecurity. While I found some good data starting in the late 90’s, I haven’t been able to find data old enough to help me answer this question (if you know of some, please pass it along.)

Again, these growth chart comparisons are naturally limited in that they compare a single day snapshot of a kid’s height and weight with smoothed averages of kids of the same age and sex (but not race, ethnicity, or any other characteristic) from 1963-1980 (or 1994 if the kid is less than 6 years old.) So, there was certainly a hint of pathologization of body size (or, at least, the desire to surveil for higher-weight bodies) but, again, it wasn’t about “diagnosing” kids as being too large.

Until it was.

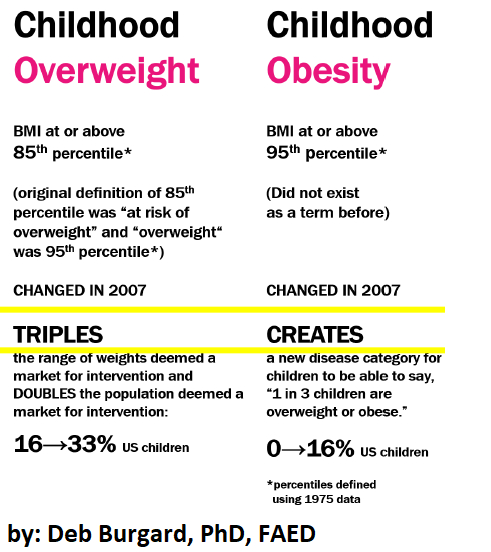

As Deb Burgard pointed out

“In terms of history, it is also helpful to note there was no category of "childhood ob*sity" before the "moral panic" of the "ob*sity epidemic" of the late-90s, early oughts - which was also an economic panic for the weight cycling industry whose products and services were being rejected by an increasingly informed public.”

So the 85th percentile became “overw*ight” which, Deb explains, “triples the range that would be pathologized” and the 95th percentile and up was now labeled “ob*se”.

Deb created the following graphic:

I also want to note that, within the growth chart methodology, there seems to be a lot of focus on this idea of labeling children as possibly too large. The word “overw*ight” appears in the text (excluding the reference list) 14 times while the word “underweight” appears only once. This may be because “underweight” was already something physicians were paying attention to, but I think it’s important to note.

It’s not that these aren’t reasonable statistical techniques if you just want a general idea of how kids grow. We always have to remember that these charts are being used on children whose very individual sizes, weights, and growth curves are influenced by myriad things.

The modern use of these charts create a situation where actual children are being judged against percentiles that artificially lowered the average weight in the data by eliminating 1/5th of thee data and eliminating any outliers left after that (even though “outliers” very much existed.) So instead of simply looking at each child’s growth trajectory individually, the healthcare system now compares them to statistically manipulated decades old data and then labels all modern kids in the 85th percentile and above as too heavy and, further, suggests (often expensive and potentially dangerous) weight management interventions.

In Part 2 we’ll dig deeper into the research and discuss what can be done.

Did you find this post helpful? You can subscribe for free to get future posts delivered direct to your inbox, or choose a paid subscription to support the newsletter (and the work that goes into it!) and get special benefits! Click the Subscribe button below for details:

Liked the piece? Share the piece!

More research and resources:

https://haeshealthsheets.com/resources/

*Note on language: I use “fat” as a neutral descriptor as used by the fat activist community, I use “ob*se” and “overw*ight” to acknowledge that these are terms that were created to medicalize and pathologize fat bodies, with roots in racism and specifically anti-Blackness. Please read Sabrina Strings’ Fearing the Black Body – the Racial Origins of Fat Phobia and Da’Shaun Harrison’s Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness for more on this.

Tangential, but since becoming a mother I have experienced so much whiplash around weight. You'll have newly post-partum women lamenting they haven't lost their "baby weight" yet while also agonizing over their baby's every ounce gained, worried that they aren't gaining weight quickly enough. I've seen mothers with low-weight infants post online about being jealous when seeing babies with fat rolls. My mother--who very much buys into diet culture--gets upset because my son is "so small" (he's been 60th percentile height and weight since birth, for reference). It's such a mindscrew for me, someone who's been fat most of her life and is used to seeing people view weight gain and fat as wholesale evil. I'm curious at what age the switch flips over to parents fretting that their kids are too big. I feel like there's a good anthropology book in here. It's weird.

I was surprised to see BMI listed on my newborn's health summary. His height, weight, and head circumference have all grown in a nice linear pattern, while his BMI is all over the place, jumping from .5% to 83% back to 36%. It does not seem like a stable or usable metric for an infant. Why is it even there?

I did find this helpful! I had no knowledge of how this new analysis of data came about but I did know it had changed in the last 30 years. I’m old enough to remember that they weren’t calling me obese as a child when I was in the 99th percentile and while the dr has never used the term I still see it written in my almost 8 yo’s chart. I logically know that he’s genetically predisposed to hit puberty early and he’s a very similar height and weight to me at his age. our second child is like his dad and right in the middle of the curve at 5 yo- he’s my child that also has a much more limited diet and it frustrates me that he gets labelled as a healthy weight and my oldest is not. They have very similar activity levels and play the same sports. My oldest also had a low birth weight and was a low percentile the first year of his life- they put him on high calorie formula that whole first year, there is so much emphasis on them growing “well” as babies.