Serious Issues With the American Academy of Pediatrics Guidelines For Higher-Weight Children and Adolescents

This is the Weight and Healthcare newsletter! If you like what you are reading, please consider subscribing and/or sharing!

The American Academy of Pediatrics has put out a new Clinical Guideline for the care of higher-weight children. This document is 100 pages long including references and there are so many things that are concerning and dangerous in it that I had trouble deciding how to divide it up to write about it.

I began on Thursday with a piece about the undisclosed conflicts of interest. Ultimately for today, I decided to focus on what I think will do the most harm in the guidelines, which is the recommendations for body size manipulation of toddlers, children, and adolescents through intensive behavioral interventions, drugs, and surgeries.

A few things before we dive in.

First, this piece is long. Really long. I thought about breaking it up to make it easier to parse, but I also know that people are (rightly) very concerned about these guidelines and I didn’t want to trickle information/commentary out over days and weeks in case it might be helpful to someone now.

Also, know that this may be emotionally difficult to read, in particular for those who have been harmed by weight loss interventions foisted on them as children. That will likely be exacerbated by the gaslighting these guidelines do to erase the lived experience of harm and trauma from the “interventions” they are recommending, and from their co-option of anti-weight-stigma language to promote weight loss. So please take care of yourself, you can always take a break and come back.

Per my usual policy I will not link to studies that are based in weight bias and the weight loss paradigm, but will provide enough information for you to Google if you want to read them. I’ll also use an asterisk in “ob*sity” for the reasons I explain in the post footer.

Ok, big breath and let’s get into this.

In later newsletters, I’ll address other issues in depth, but for now here are some quick thoughts and links about overarching issues before I dig into the actual recommendation:

The claim that “ob*sity is a chronic disease—similar to asthma and diabetes”

No, it’s really not. And it’s this faulty premise (that having a body of a certain size is the same thing as having a health condition with actual identifiable symptomology) that underlies everything in these guidelines. The diagnosis of asthma requires documentation of signs or symptoms of airflow obstruction, reversibility of obstruction (improvement in these signs or symptoms with asthma therapy) and no clinical suspicion of an alternative diagnosis. The diagnosis of diabetes requires a glycated hemoglobin (A1C) level of 6.5% or higher. But to diagnose “ob*sity” you just need a scale and a measuring tape. A group of people with this “diagnosis” don’t have to share any symptoms at all, they simply have to exist in their bodies. That is not the same as asthma or diabetes, though the weight loss industry (in particular pharmaceutical companies and weight loss surgery interests) have absolutely poured money into campaigns to try to convince us that it is. (Note that the argument that ob*sity is correlated with other health conditions and thus is a disease actually proves the fallacy since some kids/people who are “diagnosed” with “ob*sity” don’t have any of those health conditions and some kids/people who are thin do have them. It’s especially disingenuous as it ignores the confounding variables of weight stigma and, in particular, weight cycling both of which these guidelines, if adopted, are very likely to increase.) I wrote about this in-depth here.

The myth of “non-stigmatizing ob*sity care”

Like so much of these guidelines, this idea and much of the verbiage around it mirrors that of the weight loss industry. In this case, it’s attempt to co-opt the language of anti-weight-stigma in order to promote (and profit from) weight loss (there’s a guide to telling the difference between true anti-stigma work and diet industry propaganda here.) In truth, there is no such thing as non-stigmatizing care for ob*sity, because the concept of ob*sity is rooted in size and the treatment is changing size (the word was made up to pathologize larger bodies, based on a latin root that literally means to eat until fat so…less science than stereotype there.) There is no shame in having a disease, it’s just that existing while fat isn’t one. The concept of “ob*sity” as a “disease” pathologizes someone’s body size. The concept of ob*sity says that your body itself is wrong, and requires intensive therapy and/or risky drugs and surgeries so that it can be/look right. There is no way to say that without engaging in weight stigma.

If someone claims that the treatment is actually about health and not size, then it’s not “ob*sity” treatment since both the criteria for the “disease” and the measure of successful “treatment” of ob*sity are based on body size. If the treatment is about health and not size, then the treatment and measures of success should be about actual metabolic health, not body size (which would be ethical, evidence-based, weight-neutral care.)

The idea that “It is important to recognize that treatment of ob*sity is integral to the treatment of its comorbidities and overw*ight or ob*sity and comorbidities should be treated concurrently”

Again, I think this is demonstrably untrue. Any health issues that are considered “comorbidities” of being higher-weight are also health issues that thin people get, which means that they have independent treatments. We could skip body size manipulation attempts entirely and still treat any health issues that a higher-weight child/adolescent has.

The dubious claim that “ob*sity treatment” is compatible with eating disorders prevention

I wrote a specific piece about this here.

Weight loss as a “solution” to weight stigma

This is unconscionable. Regardless of what someone believes about weight and health, the message that children (as young as 2!) should solve stigma by attempting to change themselves though undertaking intensive and dangerous interventions that risk quality of life moves beyond inappropriate to disgusting, especially when one is perpetuating weight stigma, as these guidelines (and the weight loss industry talking points that are repeated herein) do.

There is so much more to unpack here, but I want to move into a discussion of the recommendations themselves.

For this, I will start where I left off on the conflict of interest piece. Which is to say, almost all of the authors of these guidelines are firmly entrenched in the body-size-as-disease paradigm. They have pinned their careers to it. None of the authors are coming from a weight-neutral paradigm. In fact, in the research evaluation methodology section, they explain that they excluded studies that looked at impacting health, rather than weight. In their own words:

The primary aim of the intervention studies had to be examination of an ob*sity prevention (intended for children of any weight status) or treatment (intended for children with overw*ight or ob*sity) intervention. The primary intended outcome had to be ob*sity, broadly defined, and not an ob*sity comorbidity.

Note that by “ob*sity comorbidity” they mean a health condition that happens to children of all sizes but is, in this instance, happening to someone higher-weight.

I don’t know if it was intentional, or just a myopic focus on body size manipulation as a supposed healthcare intervention, but the option to focus on health rather than size was specifically excluded by a group of authors whose careers on based on focusing on size.

There are three main areas of their recommendation that I’ll talk about today - Intensive Health Behavior and Lifestyle Treatment, Weight Loss Drugs, and Weight Loss Surgeries.

RECOMMENDATION: Intensive Health Behavior and Lifestyle Treatment (IHBLT)

This is recommended starting as young as age two. That’s right, they are recommending intensive interventions to kids in diapers (and they think that they should look into how to “diagnose” kids who are even younger, yikes!) What these guidelines subtly admit is that these interventions don’t actually work. They include this (long-time weight loss industry) talking point

“a life course approach to identification and treatment should begin as early as possible and continue longitudinally through childhood, adolescence, and young adulthood, with transition into adult care.”

The translation to this is that they have absolutely no idea how to make higher-weight people of any age thin long-term. They are aware (and if not they are negligent) that a century of data shows that the vast majority of people will lose weight short-term and gain it back long-term. What they seem to be trying to do here is rebrand yo-yo dieting (aka weight-cycling) as a successful intervention. If there is a prize for moving the goalpost and declaring victory, they are in the running.

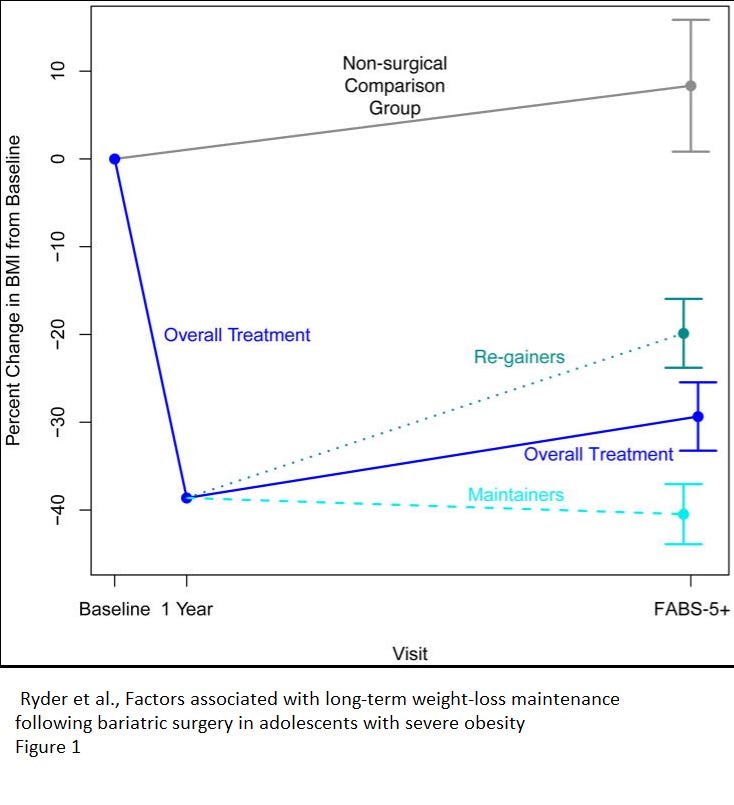

Don’t just take my word for it, they created a graphic as part of Figure 1 to show it:

Pro tip: When they say “relapsing remitting” they mean “yo-yo dieting". I know why the weight loss industry loves this idea - it’s how they’ve built a business that creates exponential growth with a product that doesn’t work. What I don’t understand is how this group of authors can possibly justify this ethically. The health risks of weight cycling are documented (and very consistent with the health risks that get blamed on higher-weight bodies) so setting people up for weight cycling starting as toddlers does not, to me, have the ring of sound science or ethical, evidence-based medicine.

Let’s dig into the evidence they are using to support this:

The guidelines claim that “IHBLT is the foundational approach to achieve body mass reduction or the attenuation of excessive weight gain in children. It involves visits of sufficient frequency and intensity to facilitate sustained healthier eating and physical activity habits.”

The study they cite to back this up (Grossman et al; 2017, Screening for ob*sity in children and adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement) says “Comprehensive, intensive behavioral interventions (≥26 contact hours) in children and adolescents 6 years and older who have ob*sity can result in improvements in weight status for up to 12 months.”

They also include a chart of seven randomized controlled trials (RCTs) from 2005-2017. The combined study population of all seven studies was just 1,153 kids. The largest study (with 549 participants) and the only study to include children from ages 2 to 5 had a duration of 12 months and showed a BMI change of 0.42 that year, and was only “effective” (if you consider a .42 change in a year “effective”) in kids ages 4-8 years old. There was only one study that followed up for more than 12 months, and from 12 months to 24 months, the BMI change decreased (from 3.3 to 2.8,) consistent with the weight regain pattern that we would expect.

This will be a running theme in these guidelines - short-term studies will be used to justify life-long recommendations, and weight regain is ignored. In general, sometimes this is based on the idea that if a weight loss intervention works short-term, then it will continue to work forever, other times it’s based on the idea that weight cycling is an ethical, evidence-based healthcare intervention. Again, the data on both the long-term failure of weight loss and the danger of weight cycling does not support this.

They make a point to mention that IHBLT “involves interaction with pediatricians and other PHCPs who are trained in lifestyle-related fields and requires significantly more time and resources than are typically allocated to routine well-child care.” At this point I’ll note that many of the authors of the guidelines run clinics or have practices that provide exactly this type of care.

Their criteria for the studies was, I’ll just call it lax: “Over a 3-12 month period: The criteria for the evidence review required a weight-specific outcome at least 3 months after the intervention started.” Obviously, this is a very short-term requirement and, again, excludes studies that looked at actual health instead of just body size.

Here again they tell on themselves

Treatments with duration longer than 12 months are likely to have additional and sustained treatment benefit. There is limited evidence, however, to evaluate the durability of effectiveness and the ability of long-term treatments to retain family engagement.

Note that the idea that longer duration treatment is “likely” to have additional and sustained treatment benefit is not remotely an evidence-based statement, and I would argue that it is biased and should not be included here. Also, they seem to be setting the stage for blaming families for the entirely predictable and almost always inevitable weight regain.

Under “referral strategies” they get real about how little weight loss we’re actually talking about:

Pediatricians and other Primary Healthcare Providers (PHCP’s) are encouraged to help to set reasonable expectations for these [BMI-based] outcomes among families, as there is a significant heterogeneity to treatment response and there is currently no evidence to predict how individual children will respond. Many children will not experience BMI improvement, particularly if their participation falls below the treatment threshold.”

As described in the Health Behavior and Lifestyle Treatment section, those who do experience BMI improvement will likely note a modest improvement of 1% to 3% BMI percentile decline.

So they are recommending an “intensive,” time-consuming, expensive intervention to kids starting as young as age 2 with no prognostics as to which kids might be “successful,” the stated result of which is that “many” (their word) of them won’t experience any change in the primary outcome, those who do will see a very small change.

They do mention the supposed actual health benefits of these interventions, but fail to mention that the health benefits may have nothing to do with the very small change in size. That’s because often when health changes and weight changes (at least temporarily) follow behavior change, those who are invested in the weight loss paradigm (financially, clinically, or both) are quick to credit the weight change, rather than the behavior change, for the health change. Here again, the evidence does not support this. It’s very possible that these same health improvements could be achieved with absolutely no focus or attention paid to weight, which would provide more benefits and less risks (including the risks associated with both weight stigma and weight cycling.) It could also allow the children (some, remember, still in diapers) to create healthy relationships with food and movement, rather than seeing choices around food and movement as punishment for their size or a way to manipulate it.

As they move into specific recommendations, they start with:

Despite the lack of evidence for specific strategies on weight outcomes many of these strategies have clear health benefits and were components in RCTs of intensive behavioral intervention. Many strategies are endorsed by major professional or public health organizations. Therefore, pediatricians and other PHCPs can appropriately encourage families to adopt these strategies.

To me this sounds a lot like throwing the concept of “evidence-based” right out the window. None of this means “these strategies are likely to lead to long-term weight loss,” but I’ll bet that won’t be what is conveyed to the patients and families upon whom these “strategies” are foisted.

Before we move on to their recommendations around diet drugs, here is some research to contextualize these recommendations:

Neumark-Sztainer et. al, 2012, Dieting and unhealthy weight control behaviors during adolescence: Associations with 10-year changes in body mass index

None of the behaviors being used by adolescents for weight-control purposes predicted weight loss

Of greater concern were the negative outcomes associated with dieting and the use of unhealthful weight-control behaviors…including eating disorders and weight gain [Note: This is not to say that there is anything wrong with higher-weight, but that there is something wrong with a supposed healthcare intervention that has significant risks, almost never works, and has the opposite of the intended effect up to 66% of the time.]

Raffoul and Williams, 2021, Integrating Health at Every Size principles into adolescent care

Current weight-focused interventions have not demonstrated any lasting impact on overall adolescent health

BEAT UK, 2020 Eating Disorders Association, Changes Needed to Government Anti-ob*sity Strategies

Government-sanctioned anti-ob*sity campaigns

increase the vulnerability of those at risk of developing an eating disorder

exacerbate eating disorder symptoms in those already diagnosed with an eating disorder

show little success at reducing ob*sity

Strategies including changes to menus and food labels, information around ‘healthy/unhealthy’ foods, and school-based weight management programs all pose a risk.

Pinhas et. al. 2013, Trading health for a healthy weight: the uncharted side of healthy weights initiatives

Ob*sity-prevention programs that push “healthy eating” are triggering disordered eating in some children, creating sudden neuroses around food in children who never before worried about their weight

They were all affected by the idea of trying to adopt a more healthy lifestyle, in the absence of significant pre-existing notions, beliefs or concerns regarding their own weight, shape or eating habits prior to the intervention

Fiona Willer, Phd, AdvAPD, FHEA, MAICD, Non-Executive Board Director at Dietitians Australia

Quoted from: health.usnews.com/health-news/blogs/eat-run/articles/for-healthy-kids-skip-the-kurbo-app

“Dieting to a weight goal was found to be related to poorer dietary quality, poorer mental health and poorer quality of life when compared with people who were health conscious but not weight conscious”

Ok. Moving on.

RECOMMENDATION: Use of Pharmacotherapy (aka Weight Loss Drugs)

Their consensus recommendation is that pediatricians and other PCHPs “may offer children ages 8 through 11 years of age with ob*sity weight loss pharmacotherapy, according to medication indications, risks, and benefits as an adjunct to health behavior and lifestyle treatment.”

They admit that “For children younger than 12 years, there is insufficient evidence to provide a Key Action Statement (KAS) for use of pharmacotherapy for the sole indication of ob*sity,” but then go on to suggest that if kids 8-11 also have other health conditions, somehow weight loss drugs (which are not indicated for the treatment of the actual health conditions they have) “may be indicated.”

Their KAS is that “pediatricians and other PHCPs should offer adolescents 12 y and older with ob*sity weight loss pharmacotherapy, according to medication indications, risks and benefits as and adjunct to health behavior and lifestyle treatment.”

The studies that were actually included in the evidence review predominantly studied metformin (alone and in combination with other drugs,) which is not approved for weight loss, orlistat, exenatide, and one study that looked at phentermine, mixed carotenoids, topiramate, ephedrine, and recombinant human growth hormone.

Even though the studies for other drugs did not exist at the time of the evidence review, they made the choice to include them anyway. (This includes Wegovy, the drug that Novo Nordisk, a donor to the AAP, has promised their shareholders will be a blockbuster and that announced its approval in children as young as 12 just days prior to the publication of the guidelines.)

Let’s look at the efficacy of the drugs they are recommending:

Metformin

Adverse effects include bloating, nausea, flatulence, and diarrhea and lactic acidosis which they characterize as “serious but very rare.” The guidelines describe the evidence of metformin for weight loss in pediatric populations as “conflicting” They evaluated 16 studies, about two-thirds of which showed a “modest BMI reduction” and one-third showed “no benefit.” Also, this drug is not approved for weight loss. They recommend that due to the “modest and inconsistent effectiveness, metformin may be considered as an adjunct to intensive health behavior and lifestyle treatment (IHBLT) and when other indications for use of metformin are present.”

Orlistat:

This drug is currently approved for ages 12 and up. Orlistat is sold under the name alli by GlaxoSmithKline and as Xenical by Genentech (both GlaxoSmithKline and Genentech are donors to the AAP.) The guidelines point out that the side effects (including fecal urgency, flatulence and oily stool) “greatly limit tolerability” but do say that “Orlistat is FDA approved for long-term treatment of ob*sity in children 12 years and older.” They cite a study from 2004 and a study from 2005. One (Behzat et al., Addition of orlistat to conventional treatment in adolescents with severe ob*sity) started with 22 adolescents, 7 of whom dropped out within the first month due to drug side effects. The remaining 15 subjects were followed for 5-15 months with an average of 11.7 months of follow up. Those 15 patients lost 6.27 +/- 5.4 kg within the study time.

The other (Chanoine JP et al, 2005, Effect of orlistat on weight and body composition in ob*se adolescents) was a one-year study with 357 adolescents (age 12-15) in the Orlistat group. They lost weight initially but the weight loss stopped at week 12 and by the end of the study the weight of those in the Orlistat group had increased by .53kg.

Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists

These are drugs that are type 2 diabetes medications that were found to have a side effect of weight loss. In some cases they have been rebranded specifically for weight loss and, in others, are prescribed off-label.

Exenatide

This drug is currently approved in kids ages 10 to 17 years of age. The guidelines point out that a small weight loss was shown in two small studies but with “significant adverse effects.”

Liraglutide

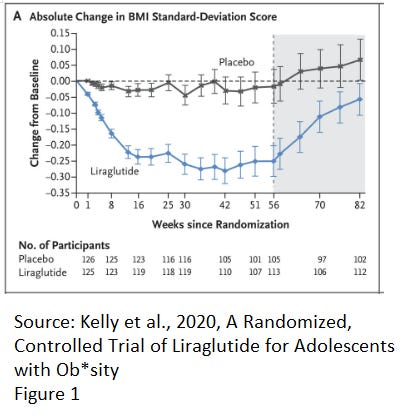

The study they cite for liraglutide (Kelly et al, Trial Investigators. A randomized, controlled trial of liraglutide for adolescents with ob*sity.) was a 56 week study with a 26-week follow-up period. Participants lost weight initially, but after 42 weeks began to regain weight (though they were still on the drug) at 56 weeks weight gain became more rapid and at the end of the 26-week follow up they were nearing baseline. The guidelines characterize this as “A recent randomized controlled trial found liraglutide (daily injection) more effective than placebo in weight loss at 1 year among patients 12 years and older with ob*sity who did not respond to lifestyle treatment.” They do not make it clear that participants experienced near total weight regain (see graphic below.)

In addition to the near total lack of weight loss (and remember that it’s pretty likely that subjects continued to regain weight after the tracking stopped at 82 weeks,) side effects included nausea and vomiting, and among patients with a family history of multiple endocrine neoplasia, a slightly increased risk of medullary thyroid cancer. Liraglutide is sold as Victoza and Saxenda by Novo Nordisk. This study was a clinical trial funded by Novo Nordisk, multiple study authors work for, are employees of, take payments from and/or own stock in Novo Nordisk (see disclosures below) and Novo Nordisk provides funding directly to the American Academy of Pediatrics, and has paid thousands of dollars to authors of these guidelines.

Just for funsies I checked the disclosures: Dr. Kelly reports receiving donated drugs from AstraZeneca and travel support from Novo Nordisk and serving as an unpaid consultant for Novo Nordisk, Orexigen Therapeutics, VIVUS, and WW (formerly Weight Watchers); Dr. Auerbach, being employed by and owning stock in Novo Nordisk; Dr. Barrientos-Perez, receiving advisory-board fees from Novo Nordisk; Dr. Gies, receiving advisory-board fees from Novo Nordisk; Dr. Hale, being employed by and owning stock in Novo Nordisk; Dr. Marcus, receiving consulting fees from Itrim and owning stock in Health Support Sweden; Dr. Mastrandrea, receiving grant support from AstraZeneca and Sanofi US and grant support and fees for serving on a writing group from Novo Nordisk; Ms. Prabhu, being employed by and owning stock in Novo Nordisk; and Dr. Arslanian, receiving fees for serving on a data monitoring committee from AstraZeneca, fees for serving on a data and safety monitoring board from Boehringer Ingelheim, grant support, paid to University of Pittsburgh, and advisory-board fees from Eli Lilly and Novo Nordisk, and consulting fees from Rhythm Pharmaceuticals.

Melanocortin 4 receptor (MC4R) agonists

These are specialty drugs that are only FDA approved for patients 6 years and older with proopiomelanocortin deficiency, proprotein subtilisin or kexin type 1 deficiency and leptin receptor deficiency confirmed by genetic testing. They site a small, uncontrolled study in which patients experience weight loss of 12-25% over 1 year.

Phentermine

Phentermine is a controlled substance chemically similar to amphetamine which carries a risk of dependence as well as side effects including elevated blood pressure, dizziness, and tremor. These are FDA approved for a 3-month course of therapy for adolescents 16 or older. I’m not clear what good could come out of giving a teenager a drug with these kinds of risk for 3 months?

Topiramate

This is a drug that is used to treat seizures and migraines that happens to have a side effect of making people not want to eat through what the guidelines admit are “largely unknown mechanisms.” These drugs cause cognitive slowing and can cause embryo malformation. It’s approved for children 2 years and older with epilepsy and 6 and older for headaches and I cannot for the life of me imagine how it could possibly be ethical to cause cognitive slowing in a child (who is going to school!) in order to disrupt their bodies hunger signals.

Phentermine/Topiramate

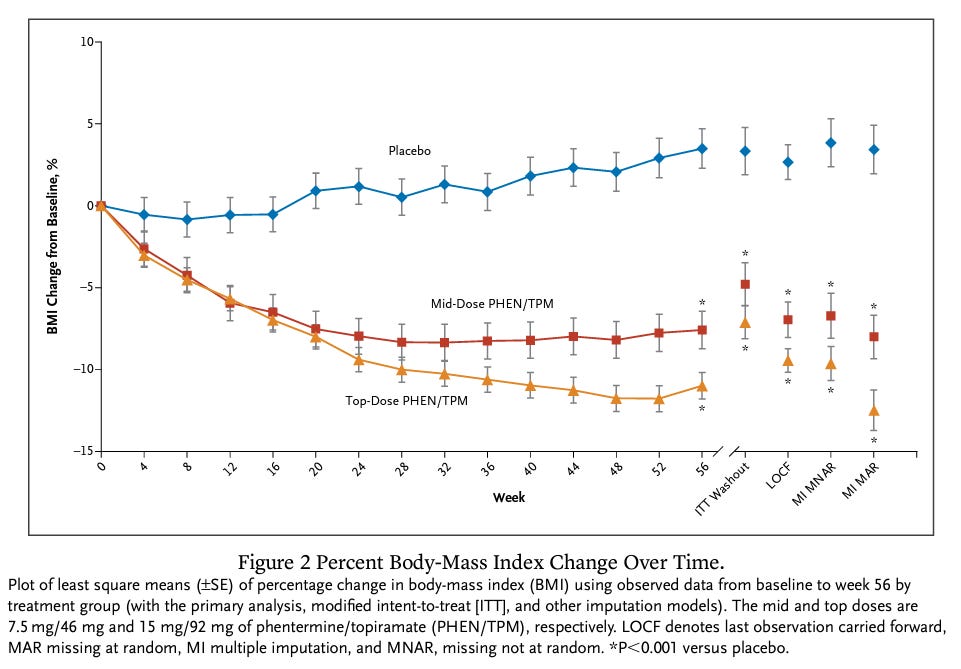

You read that right, those last two drugs with the dangerous, quality-of-life impacting side effects? The guidelines discuss the option of prescribing them together. To children. This is based on a 56-week study (Kelly et al, 2022, Phentermine/topiramate for the treatment of adolescent ob*sity.) In the study, 54 subjects were given a mild dose, 15 of them dropped out. 113 were given the “top dose” 44 of them dropped out. As we’ve seen in other studies, weight loss had leveled off and begun to rise slightly by week 56 and there is no reason to believe it wouldn’t go back up, but we’ll never know because they didn’t do any more follow-up. By the way, like most of the other studies, these subjects were also undergoing a “lifestyle modification program.” Also, like the other drugs, I think it’s important to note that this was FDA-approved for “chronic treatment” based on the results of a study that only lasted 56 weeks. That is a common situation with weight loss drugs.

Finally, the guidelines don’t mention that side effects of this drug include increased heart rate, suicidal behavior and ideation, slowing of linear growth, acute myopia, secondary angle closure glaucoma, visual problems; mood and sleep disorders; cognitive impairment; metabolic acidosis; and decrease in renal function.

As I was looking this up, I noticed that the lead author of this study is the same lead author of the liraglutide study. Phentermine/Topiramate is sold under the brand name Qysmia by Vivus. I had to do some digging to get to the disclosures on this one and what do you know, Dr. Kelly has received grant consideration and consults for Vivus. In fact, with the exception of Megan Oberle, every author of this study either receives funding from/consults for Vivus, or is an employee of Vivus. Megan Oberle lists no conflicts of interest in this 2022 study but, interestingly, in a 2019 study (It is Time to Consider Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes in Youth) the disclosure states “MO serves as site PI [principal investigator] for study through Vivus Pharmaceuticals” so we know they’re not strangers.

Lisdexamfetamine

This is a stimulant that is approved for kids 6 and older who have ADHD, in those 18 and up for Binge Eating Disorder, and while it is sometimes prescribed off-label for higher-weight kids, the guidelines note that “no evidence available at the time of this review to demonstrate safety or efficacy for the indication of ob*sity in children.”

Summing up, there are significant risks of side effects (some life threatending) and not a drug among them has shown anything approaching long-term efficacy.

Let’s look at the last of the recommendations.

RECOMMENDATION: Weight Loss Surgery

This is the last bit I’ll write about today. This section begins

It is widely accepted that the most severe forms of pediatric ob*sity (ie, class 2 ob*sity; BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2, or 120% of the 95th percentile for age and sex, whichever is lower) represent an “epidemic within an epidemic.”

Remember, for a moment, that this phrasing is from authors who swear up and down that they are working to end weight stigma. One wonders what they would have written if they were trying to stigmatize higher-weight children. (Just fyi, if anyone is confused, you can’t usefear-mongering language, describing a group of people simply existing in the world at a higher-weight as an “epidemic” without stigmatizing them.)

The KAS here (for me the most horrifying of those offered,) is

Pediatricians and other PHCPs should offer referral for adolescents 13y and older with severe ob*sity (BMI ≥ 120% of the 95th percentile for age and sex) for evaluation for metabolic and bariatric surgery to local or regional comprehensive multidisciplinary pediatric metabolic and bariatric surgery centers. [I’ll note here that at least one of the authors of these guidelines runs just such a facility.]

Before we get too far into this, let’s be clear about what these surgeries do. They take a child’s perfectly functioning digestive system, and put it into a (typically irreversible) disease state forcing, restriction and/or malabsorption (for an explanation of the various surgeries, check out this post.) If this state happens to a child because of disease or accident, it is considered a tragedy. If the child is higher-weight, it is considered, at least by the authors of these guidelines, healthcare.

They make the claim

“Large contemporary and well-designed prospective observational studies have compared adolescent cohorts undergoing bariatric surgical treatment versus intensive ob*sity treatment or nonsurgical controls. These studies suggest that weight loss surgery is safe and effective for pediatric patients in comprehensive metabolic and bariatric surgery settings that have experience working with youth and their families”

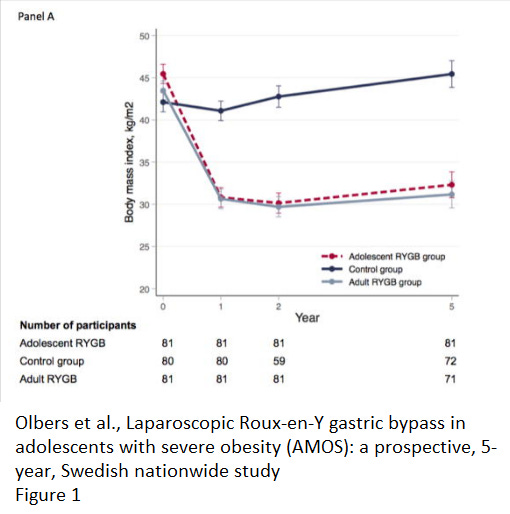

To support this, they cite a single study. The study (Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in adolescents with severe ob*sity (AMOS): a prospective, 5-year, Swedish nationwide study) included 81 subjects who underwent Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

The average weight loss was 36·8 kg over five years, but 11% of those who had the surgery lost less than 10% of their body weight.

A full 25% had to have additional abdominal surgery for complications from the original surgery or rapid weight loss and 72% showed some type of nutritional deficiency. And that’s just in five years. Remember that the damage done to the digestive system is permanent. They are recommending this as young as 13, so a five year follow-up only gets these kids to 18. Then what?

By the look of their own graph, what comes next may well be more weight gain, since the surgery survivors’ weight loss leveled off after year one and started to steadily climb after year two. There’s also the impact of those nutrient deficiencies.

They also claim that these surgeries lead to a “durable reduction of BMI.” Let’s take a look at the studies they cite to prove that.

Inge et al., 2018 Comparison of Surgical and Medical Therapy for Type 2 Diabetes in Severely Ob*se Adolescents

This study lasted two years. It looked at data from 30 adolescents who had weight loss surgery. They averaged 29% weight loss over 2 years and 23% of the subjects had to have a second surgery during those two years.

Göthberg et al., 2014, Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in adolescents with morbid ob*sity--surgical aspects and clinical outcome

This study just rehashes information from the Olbers study above.

O’Brien et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in severely ob*se adolescents: a randomized trial

This study is about gastric banding and I’m not sure why they included it because in the paragraph above it they point out that these surgeries are “approved by the FDA only for patients 18 years and older, have declined in use in both adults and youth because of worse long-term effects as well as higher-than expected complication rates” (they cite 18 studies to back up this particular claim.)

Olbers et al., 2012 Two-year outcome of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in adolescents with severe ob*sity: results from a Swedish Nationwide Study (AMOS)

These are just the two-year outcomes from the five-year Olbers study above

Olbers et al. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in adolescents with severe ob*sity (AMOS): a prospective, 5-year, Swedish nationwide study.

This is the exact same 5-year Olbers study from above, just given a different citation number.

Ryder et al., 2018 Factors associated with long-term weight-loss maintenance following bariatric surgery in adolescents with severe ob*sity

This study included 50 subjects who had Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and had a follow-up at year one and another follow-up sometime between years 5 and 12. They were then divided into “regainers” and “maintainers” though by their criteria, “maintainer” subjects could regain, they just couldn’t regain more than 20% of the weight they lost prior to their follow-up. Though the study is called “Factors associated with long-term weight-loss maintenance” they were not able to identify any factors that were predictors of “regaining” or “maintaining.” You’ll note in the graph below that weight was still trending upward when they stopped following up.

So let’s recap: They cite 7 studies to back up their recommendation of referrals for these surgeries for kids ages 13 and up. Four of the seven are the same study. One is a study for a surgery that they themselves have said is declining in use, so I’m excluding it. Combined, the rest of the studies followed a grand total of 161 people. The longest follow-up is “5+ years” and the studies consistently showed weight regain that was trending up when follow-up ended, as well as high rates of additional surgery and nutrient deficiencies. This, to me, doesn’t come close to justifying a blanket recommendation that every kid 13 and older whose BMI ≥ 120% of the 95th percentile for age and sex be referred for evaluation for weight loss surgery.

And when it comes to their criteria for these surgeries, they predicate risk on size. Those with “class 2 ob*sity” are required to have “clinically significant disease” which doesn’t make the surgery ethical but, in comparison; children with “class 3 ob*sity” simply have to exist in the world to meet the criteria to have their digestive system put into a permanent disease state.

One thing they do point out is that recent data showing multiple micronutrient deficiencies following metabolic and bariatric surgery serve to highlight the need for routine and long-term monitoring. Here we see a serious issue with giving this surgery to adolescents. First of all, they are rarely in control of their access to food. If their parents don’t buy them what they need, if a parent loses their job and can no longer afford the supplements they require, if they experience hunger and/or homelessness… there are so many things that could impact a 13-year-old’s ability to eat in the very specific ways they need to after the surgery for the rest of their life.

Also, these surgeries are going to change the ways that these kids eat - at every school lunch, birthday party, family holiday. Anytime food is served, it is going to become clear that they are different, and if they aren’t in charge of preparing the food, there is no guarantee that they will be able to get what they need. And that’s if they want to do that. Let’s not forget, these are humans who are/will be exploring their independence, including through rebellion, they are humans whose prefrontal cortex is not fully developed, meaning that they can literally lack the ability to fully recognize the consequences of their choices. (Of course, given that we only have five years of follow-up data, I would argue that their doctors and surgical teams also lack the ability to fully recognize the consequences of their choices.)

The authors end the section with a fairly shameless plug for insurance coverage of these surgeries. This is another long-time goal of the weight loss industry that has made its way into these guidelines.

I think this is a good time for a reminder that thin kids get the same health issues for which higher-weight kids are referred to these surgeries and thin kids are NOT asked to take the risks of these surgeries or to have their digestive systems permanently altered. They just get the ethical, evidence-based treatment for the health issue they actually have.

Also, remember that the authors’ research methodology specifically excluded research about weight-neutral intervention to see if any health benefits that the surgeries might create could be achieved without the significant (and, from a long-term perspective, largely unknown) risks of these surgeries, and perhaps be more lasting?

But there is more to this in terms of informed consent. There are many of the same issues that we see with adults (which I wrote about here). With kids, there is another layer. In the state of California, for example, it is illegal to give a tattoo to someone under the age of 18, even with parental permission. But an eighth grader can make the decision to have their digestive system permanently altered, impacting their life and quality of life in myriad ways, many of which are unknown, and with no prognostics? Given all of this, is informed consent even possible for these kids? I would argue that it is not.

Even worse, how many kids’ parents, in some combination of weight stigma, concern for their child, and acquiescence to a doctor who may be pressuring them, will make this decision for their child?

While I’m sure that there are adolescents who had the surgery and are happy with their outcome, I’m equally sure that there are adolescents who had terrible outcomes and would give anything to not have had the surgery (I know because I hear from them). And I know that the research can’t tell us why anyone has the outcome they have. When you combine that with the total lack of long-term follow-up (I’m completely unwilling to consider 5 years “long term” for a lifelong intervention,) I think what we have here are, at best, experimental procedures, not procedures that should receive the kind of blanket recommendations that these guidelines provide for kids as young as 13.

Ok, there’s a lot more to discuss in these guidelines but I will save that for another newsletter. I hope that the outcry against these guidelines is loud, sustained, and successful in getting them rescinded. Kids deserve far better than this.

Finally, I just want to give a quick shout-out to my paid subscribers (I know not everyone can/wants to have a paid subscription and that’s totally fine - absolutely no shame at all if you are reading this for free as a subscriber or randomly!) those who are able to pay are allowed me to spend HOURS this week going through these guidelines and creating Thursday’s post and this post, I’m just super grateful for the support.

I’ll be posting additional deep-dives into the research they cite and I’ll keep a list here:

“New insights about how to make an intervention in children and adolescents with metabolic syndrome” Pérez et al.

Did you find this post helpful? You can subscribe for free to get future posts delivered direct to your inbox, or choose a paid subscription to support the newsletter and get special benefits! Click the Subscribe button below for details:

Liked this piece? Share this piece:

More research and resources:

https://haeshealthsheets.com/resources/

*Note on language: I use “fat” as a neutral descriptor as used by the fat activist community, I use “ob*se” and “overw*ight” to acknowledge that these are terms that were created to medicalize and pathologize fat bodies, with roots in racism and specifically anti-Blackness. Please read Sabrina Strings Fearing the Black Body – the Racial Origins of Fat Phobia and Da’Shaun Harrison Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness for more on this.

I really appreciate this longer dive!

Man, talk about telling on yourself. Imagine reading "With intensive interventions, asthmatics can improve lung function by 1%-3%". Nobody's going to go to that much work for that little. I don't know if this is audacity or stupidity...I'm not even sure which one is worse.

Thank you, thank you and thank you!

I’m a pediatric dietitian working in GI. I support a clinic with one of our providers who “specializes in nutrition” and these new guidelines scare me for what is to come. I never wanted to work in the “weight loss” or “bariatric” realm and have been forced into it and I see the harm that many well-intentioned physicians inflict on children and families along with a system that lacks proper support. I have patients come for evaluation of bariatric surgery and even one who follows post surgery (even after the RD and MD in GI did not deem them an appropriate candidate) who in later teen years now has nutritional deficiencies due to a lack of following the required dietary needs/supplementation. I hope to have a conversation with my physician group on how these recommendations fall short of being appropriate and a greater need for weight neutrality in approaching children and families in larger bodies. I hope to use some of your analysis on this article (which I’m still reading) to help them understand the risk for harm AAP guidelines can now cause.

Again thank you!