This is the Weight and Healthcare newsletter! If you like what you are reading, please consider subscribing and/or sharing!

This is the final in a three-part series about Tirzepatide (Brand name Mounjaro for Type 2 diabetes and Zepbound for Weight Loss.) In part one we discussed the basics of the drug, in part 2 we discussed the authors of this study and finally, in part three we’ll finish discussing the most recent study on Zepbound - SURMOUNT -4.

(the text in italics is from the study itself.)

SURMOUNT-4 was designed to find out what happens when higher-weight people (without type 2 diabetes) go on the drug for a while and then go off of it. The study was divided into two periods In the first 36 weeks all of the participants took Tirzepatide. Then there was a 52-week period during which subjects were randomly assigned to receive either tirzepatide, or a placebo.

The basic findings, per the study:

After 36 weeks of open-label maximum tolerated dose of tirzepatide (10 or 15 mg), adults (n = 670) with obesity or overweight (without diabetes) experienced a mean weight reduction of 20.9%. From randomization (at week 36), those switched to placebo experienced a 14% weight regain and those continuing tirzepatide experienced an additional 5.5% weight reduction during the 52-week double-blind period.

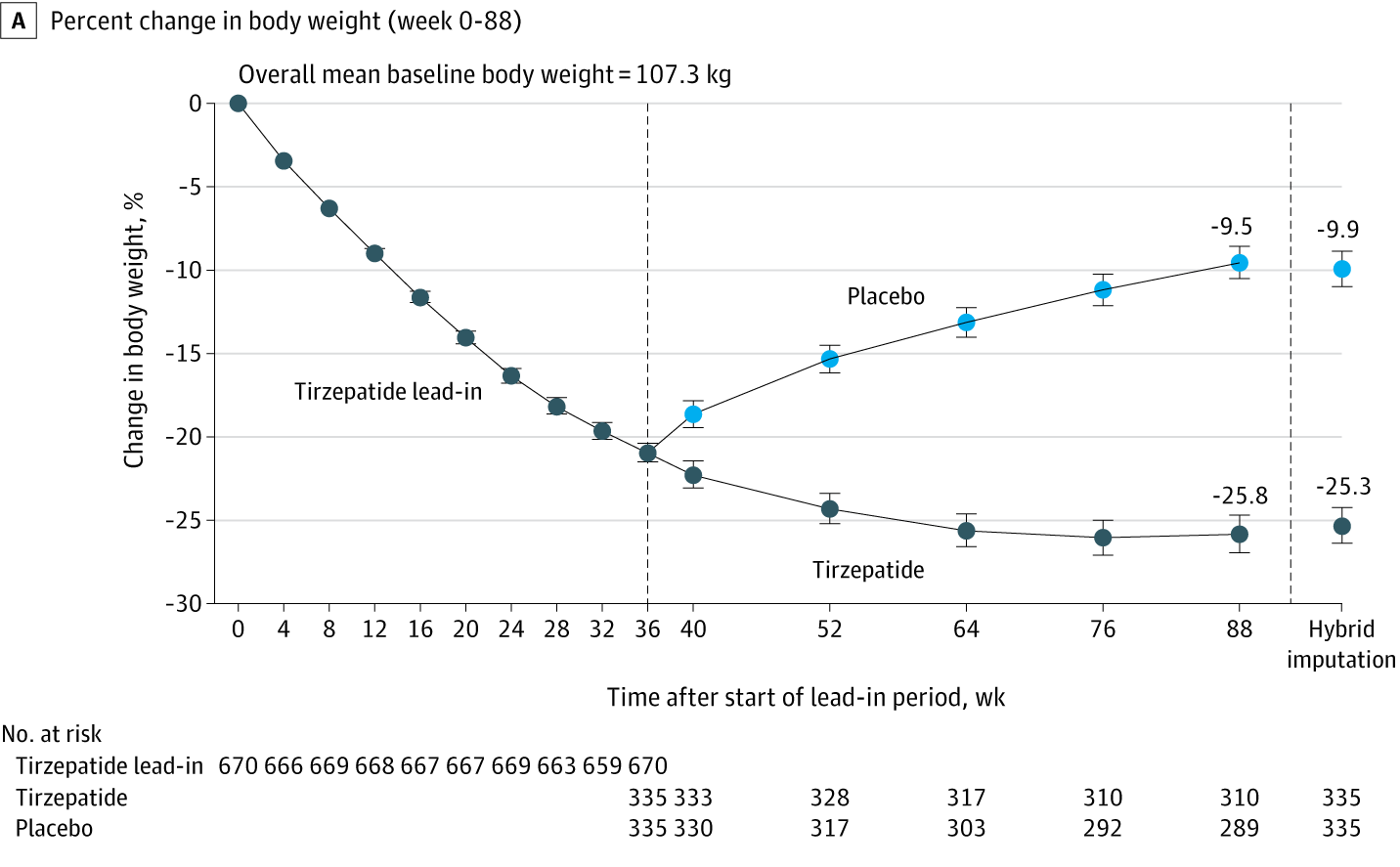

Here's a graph that shows the average results:

Some things to note:

First, the graph clearly shows that people who go off the drug rapidly start regaining the weight they lost, and their weight was trending up when follow-up ended, suggesting that the weight regain will continue (as we’ve seen in about a century of research and in the history of weight loss drugs.) In addition to being exposed to the side effects of these drugs (some of which can be fatal) these people will also be subjected to the risks that come from weight cycling which include everything from increased risk of type 2 diabetes and hypertension to increased cardiovascular disease and overall mortality. This is important since there are any number of reasons why someone would have to go off the drug, from side effects, to expense, to availability.

For those who remained on the drug, weight loss slowed considerably and by the end, had started to rise slightly, which means that the claim that weight loss will be permanent as long as people stay on the drug is not supported by the evidence.

Let’s go beyond average results and get into some specifics - 783 participants were enrolled in the initial 36-week study in which all participants took Tirzepatide, but 113 discontinued the study drug before the 36-week stage even ended, most commonly due to an adverse event or participant withdrawal. So a little over 14% didn’t even make it 9 months on the drug, and that’s including the fact that the drug was started at a minimal 2.5mg dose and then increased by 2.5 mg every 4 weeks until a maximum tolerated dose of 10 or 15 mg was achieved.

300 participants (89.5%) receiving tirzepatide at 88 weeks maintained at least 80% of the weight loss during the lead-in period

Did you catch that? First, 10.5% of the group who were still taking the drug during the one-year follow-up had already gained back more than 20% of the weight they lost in the first 36 weeks- again even though they were Still. Taking. The. Drug. As for the rest, they could well have been regaining the weight because of the way the study defined “maintaining.” For the purposes of this study, “maintaining” weight loss doesn’t mean that people lost weight and kept it off (as the word would be used in any reasonable context.) For this study, “maintained” just meant that they were regaining the lost weight slowly enough that by 52 weeks these participants hadn’t regained 20% of the weight that they lost in the first 32 weeks…yet. (This is one of those examples of words having different meanings in weight loss research.)

Let’s take a look at side effects:

A total of 81.0% of participants reported at least 1 treatment-emergent adverse event during the tirzepatide lead-in treatment period, with the most frequent events being gastrointestinal (nausea [35.5%], diarrhea, [21.1%], constipation [20.7%], and vomiting [16.3%]… [During the follow up period] Gastrointestinal events were more common in the tirzepatide group than in the placebo group (diarrhea, 10.7% vs 4.8%; nausea, 8.1% vs 2.7%; and vomiting, 5.7% vs 1.2%)

Of course, the trial wasn’t long enough to determine long-term impacts.

They also say :

A significantly greater percentage of participants continuing tirzepatide vs placebo met the weight reduction thresholds of at least 5% (97.3% vs 70.3%), at least 10% (92.1% vs 46.2%), at least 15% (84.1% vs 25.9%), and at least 20% (69.5% vs 12.6%) from week 0 to week 88

Let’s say the above another way: 2.7% of people who took Tirzepatide for 88 weeks, opening themselves up to side effects and unknown long-term consequences failed to lose even 5% of their body weight, 7.9% failed to lose even 10%, 15.9% failed to lose 15% and 30.5% failed to lose 20%. This is important since they are touting the mean weight loss as 25.3% in their results section. That’s the kind of thing that healthcare providers should include in an informed consent conversation.

The study group is also problematic in terms of extrapolation. Study findings can only be reliably applied to people in the demographics that were studied. In this case, the randomized participants were 70.6% cis women and there was no trans or non-binary representation. The mean age was 48 and the participants were 80.1% white despite having study sites at “70 sites in Argentina, Brazil, Taiwan, and the US.” In fact, the study states “The study was not designed to represent the racial diversity of each of the participating countries.” This, to me, is unconscionable – if you can’t get a more representative sample than this, then just don’t proceed with the study until you can.

The lack of a weight-neutral comparator group is also an issue. Research suggests that weight-neutral, health-supporting behaviors can have more health benefits with far less risk than intentional weight loss, including with diet drugs. By comparing their drug to a “placebo group” that is still attempting intentional weight loss, just without pharmaceutical support, they are stacking the deck, taking advantage of the fact that they KNOW that behavioral weight loss interventions don’t work long-term (they literally admit that in their introduction.) It also allows them to avoid a comparison of the actual health impacts of their drugs against the health impacts of a weight-neutral health intervention – including the difference in risk.

So, does the conclusion say that about 10% of people who take the drug can expect to lose weight over the first 36 weeks and then regain more than 20% in the next 52 weeks? Does it say how many others were slowly regaining weight, though they hadn’t (yet) regained 20% after a year?

No.

They conclude:

“In participants with ob*sity or over*eight, withdrawing tirzepatide led to substantial regain of lost weight, whereas continued treatment maintained and augmented initial weight reduction.”

That, I would suggest, is what happens when Eli Lilly and Company are involved in the study design and conduct; data collection, management, analyses, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication, and almost every listed author is either taking money from them, or is directly employed by them.

Let me offer an alternative suggestion as to what may have happened here: Participants joined this study, ostensibly, because they wanted to lose weight. They took a drug for 36 weeks that disrupted their natural sense of hunger and satiety and their natural digestive processes while (if we take their claims at face value) eating 500 calories a day less than their bodies need to properly function while exercising 150 minutes or more per week.

At 36 weeks, the drug is withdrawn from some participants whose bodies then return to their normal function and try desperately to return to stasis (which is a process that we see in non-drug induced weight loss from behavioral interventions when, after about a year of weight loss people begin to regain weight, with the vast majority regaining all of the weight they lost.)

Remember, too, that they know they are part of a trial and that they may continue getting the trial drug, or they may be getting a placebo. As almost anyone who has attempted behavior-based intentional weight loss (aka dieting) can tell you: trying to exercise while restricting food is very unpleasant, more so for this group now that their natural sense of hunger is not experiencing drug-induced interference. The fact that they no longer feel sick after their injection and/or that they can once again experience natural hunger means that they are likely aware that they are in the placebo group. They regain the weight they lost rapidly because of their body's natural reaction to being under-nourished (changing physiologically to become a weight regaining/weight maintaining machine) and the fact that their digestion is no longer impaired and their hunger is no longer suppressed.

Meanwhile, another group is kept on the hunger and digestion-disrupting drug. Their weight loss slows dramatically at 52 weeks and, for many, begins to reverse by the end of 72 weeks. This is perhaps their body finally being able to overcome the drug-induced food deprivation they’ve been experiencing. There is no reason not to expect continued weight gain if these patients are tracked beyond 72 weeks (which, since the company funding the research is the company that wants people to take the drug, seems unlikely to me.)

Again, everything about this study is designed to overstate the drug’s effectiveness, and that’s not surprising given the drug manufacturer’s deep participation in every aspect of the study which is why, with weight loss interventions, it’s always buyer beware.

Did you find this post helpful? You can subscribe for free to get future posts delivered direct to your inbox, or choose a paid subscription to support the newsletter (and the work that goes into it!) and get special benefits! Click the Subscribe button below for details:

Liked the piece? Share the piece!

More research and resources:

https://haeshealthsheets.com/resources/

*Note on language: I use “fat” as a neutral descriptor as used by the fat activist community, I use “ob*se” and “overw*ight” to acknowledge that these are terms that were created to medicalize and pathologize fat bodies, with roots in racism and specifically anti-Blackness. Please read Sabrina Strings’ Fearing the Black Body – the Racial Origins of Fat Phobia and Da’Shaun Harrison’s Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness for more on this.

Ragen, thanks for your work. I don't know if you follow Atlantic, but they have had a number of articles about GLP-1 drugs. Sharing a link for this one which notes some of the particular hazards for older adults, including massive muscle loss. Would be interested to hear your comments on this.

https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2024/02/ozempic-weight-loss-older-americans-boomers/677371/?gift=gTlVSftaM6-i5ogW0lWDl2W4A52NlO4PPWdrkXr2ae8&utm_source=copy-link&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=share

Thank you for your thorough writing. It always grounds me in my body again.