Wegovy’s So-Called “Long-Term” Study

Two-year effects of semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity: the STEP 5 trial by Garvey et al.

This is the Weight and Healthcare newsletter! If you like what you are reading, please consider subscribing and/or sharing!

To begin, I want to thank Deb Burgard for her help with this piece. She is quoted below and was kind enough to review and give feedback on the piece and I am incredibly grateful. Let’s get to it.

“Two-year effects of semaglutide in adults with overweight or ob*sity: the STEP 5 trial” by Garvey et al. claims to have “assessed the efficacy and safety of once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide 2.4 mg versus placebo (both plus behavioral intervention) for long-term treatment of adults with ob*sity, or overweight with at least one weight-related comorbidity, without diabetes”.

Before we even get into the results, let’s unpack this statement.

First, semaglutide is sold for weight loss by Novo Nordisk under the brand name Wegovy.

By “long-term” they actually mean just 104 weeks (aka 2 years.) This is an example of “long-term” meaning whatever the study authors decide it means.

Also note that, as is often the case, risk is predicated on size, putting those of higher weights at greater risk: If someone is “overw*ight” then they have to have a “weight-related comorbidity” (which is simply a health issue that people of all sizes get, that gets called “weight-related” when fat people have it) in order to qualify for the drug. But if you are in the “ob*se” category, you qualify for this drug (and its many risks,) without any health conditions – simply because you happen to be higher-weight.

In addition to the study being funded by Novo Nordisk, the author conflict of interest statement is literally longer than the study abstract. I’m going to print it here in its entirely because I think it’s worth knowing who is behind this work, emphasis is mine:

W.T.G. reports a grant from Novo Nordisk; serving as site principal investigator for the current clinical trial, which was sponsored by his university during the conduct of the study; and receiving grants to serve as site principal investigator for other university-sponsored clinical trials funded by Eli Lilly & Company, Lexicon, Epitomee and Pfizer outside the submitted work. He also served as a compensated consultant on advisory committees for Alnylam, Amgen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Fractyl and Novo Nordisk, and a volunteer uncompensated consultant on advisory committees for Boehringer Ingelheim, Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Novo Nordisk and Pfizer.

R.L.B. reports research grant support, on behalf of their institution, from Novo Nordisk and advisory/consultancy fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly & Company, Gila Therapeutics Inc, GLW-01, International Medical Press, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer and ViiV.

M.B. is an employee of Novo Nordisk A/S.

S.B. served as site principal investigator for the clinical trial (he received no financial compensation, nor was there a financial relationship) and reports advisory/consulting fees and/or other support from Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly & Company, Guidotti Laboratories, Menarini Diagnostics, Novo Nordisk and Therascience Lignaform.

L.N.C. is an employee of Novo Nordisk A/S.

J.P.F. reports research support grants from Akero, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, 89bio, Eli Lilly & Company, Intercept, IONIS, Janssen, Madrigal, Metacrine, Merck, NorthSea Therapeutics, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Oramed, Pfizer, Poxel and Sanofi; and advisory/consultancy fees from Akero, Altimmune, Axcella Health, Becton Dickenson, Boehringer Ingelheim, Carmot Therapeutics, Echosens, 89bio, Eli Lilly & Company, Gilead, Intercept, Metacrine, Merck, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer and Sanofi.

E.J. reports grants from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, FAES, Janssen, Eli Lilly & Company, MSD, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Sanofi, Shire and UCB; personal fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, FAES, Helios-Fresenius, Italfármaco, Eli Lilly & Company, MSD, Mundipharma, Novo Nordisk, UCB and Viatris.

K.K. is an employee of Novo Nordisk A/S.

G.R. reports personal (advisory/consultancy and lecture) fees and nonfinancial support from iNova Pharmaceuticals, Nestle HealthScience and Novo Nordisk; personal (lecture) fees from Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic (formerly Covidien), Merck Sharpe & Dohme, ReShape Lifesciences (formerly Apollo-Endosurgery and Allergan Australia) and W.L. Gore Device Technologies.

T.A.W. serves on advisory boards for Novo Nordisk and WW (formerly Weight Watchers), and has received grant support, on behalf of the University of Pennsylvania, from Novo Nordisk and from Epitomee Medical Ltd (the latter outside of the submitted work).

S.W. reports research funding, advisory/consulting fees and/or other support from AstraZeneca, Bausch Health Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim, CIHR, Janssen, Eli Lilly & Company and Novo Nordisk.”

Whew.

Alright, let’s dig into what they found. Here is the short answer:

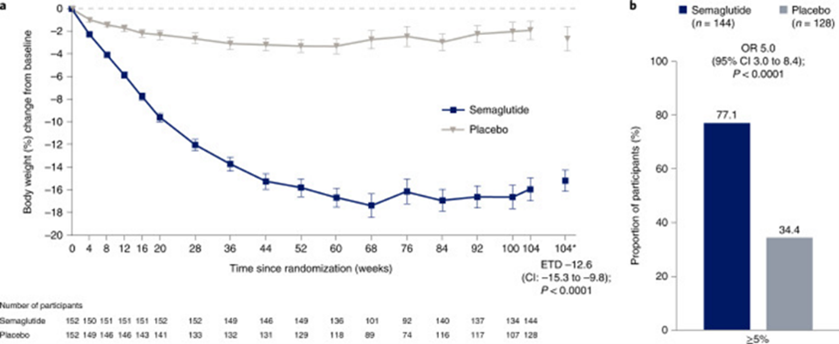

This is a graph of percentage of body weight change over the 104 weeks. I would characterize these results as: weight cycling began at week 68 and weight was trending up at week 104.

You may not be surprised to learn that the study authors (all of whom, remember, take money from Novo Nordisk) characterized it differently: “semaglutide treatment led to substantial, sustained weight loss over 104 weeks versus placebo.”

Let’s talk about the study population. They were predominantly [cis] female” (with no trans or nonbinary representation) and overwhelmingly white (92.8%.) The trial started with 152 people taking 2.4mg of semaglutide. Twenty discontinued the treatment (but remained “in the trial”), 10 for adverse effects, 2 for lack of efficacy, 1 was eliminated by the investigators for “safety concerns,” 3 were lost to follow up, 3 for “other” reasons, and 1 became pregnant (which is a larger issue since the ways that Wegovy may impact pregnancy are not known, which becomes an issue for a drug that is meant to be taken for the duration of a person’s life). Four actually withdrew from the trial (3 were “lost to follow-up” and 1 died.)

At the end of the trial 132 of the original 152 completed treatment but 5 of those had dropped down to a dose of 1.7 to less than 2.4mg, and 7 had dropped to a less than 1.7mg dose. 148 were considered to have “completed the trial” defined as attending the end of trial visit.

In terms of adverse events, 146 subjects (96.1%) experienced an adverse event, there were a total of 1,606 adverse events over the 2 years. 12 participants (7.9%) experienced a total of 18 serious adverse events. And remember, this is in just two years, people are supposed stay on this drug for their entire lives. Nine subjects (5.9%) experienced a total of 12 adverse events that led to discontinuing the product. Six subjects (3.9%) experienced “gastrointestinal disorders.”

Interestingly, they break this up into “events per 100 patient years” In terms of total adverse events, the total is 532.3 per 100 patient years. For serious adverse events, it’s 6 per 100 patient years. For adverse events that lead to discontinuation it’s 4 per 100 patient years.

This may not seem like a lot until you think about the fact that people are meant to take these drugs for the rest of their lives (and if they stop, Novo’s own study shows rapid weight regain and loss of cardiometabolic benefits.) The average age of the semaglutide group in this trial was 47.3, but remember that the disastrous AAP guidelines suggest starting children on these drugs as young as 12. Even if we assume a life expectancy of just 70 years, someone who starts the drug at 47.3 could have 22.7 patient years, which averages out to 121 adverse events, 1.32 serious events, and .9 events that lead to product discontinuation. A child who starts the drug at 12 could individually have 58 patient years with an average of 308 total adverse events, 3.48 serious adverse events, and 2.32 events that lead to product discontinuation.

This is extra concerning to me given the number of people I’m hearing and seeing in interviews (many who are on the Novo Nordisk’s payroll) extolling the safety of these drugs.

There’s also some smoke and mirrors in the discussion section for us to take a look at:

Weight loss of ≥5%, a threshold widely used to indicate a clinically meaningful response to therapy

The idea that 5-10% weight loss is “clinically meaningful” does not actually come from clinical trials but from attrition and weight loss industry fantasy land. I wrote this is depth here.

Also, as Deb points out

“people know they're going to be weighed, so even when they have regained weight when they went off the drug, they can restrict again before the weigh-in. If the standard is 5% loss, that is 12 pounds for 240# person. But it doesn't mean that the results are because of the drug. Paul Ernsberger wrote about this issue, that when the standard is so low, you are basically measuring weight cycling because people know their weigh-in date and restrict in advance of it.”

When it comes to those who are going on the drug in an attempt to “make weight” because a BMI-based procedure denial is holding their healthcare hostage for a weight loss ransom, Deb breaks down the numbers to see what the outcomes are for the higher weight people in the sample:

In order to make these numbers more meaningful. I took the participant average weight of 231# and the average BMI of 38.6, and then calculated 5% (11.5#), 10% (23#) and what appears to be the amount of loss at two years (about 16%, 37#) for 50% of the sample. Imagine this average participant, whose BMI started at 38.6, whose resulting BMI is now 32.3. If they are being denied surgery due to "ob*sity," this amount of weight loss would not even remove them from the "ob*se" BMI category (which starts at 30). If this data were being used for informed consent, one might say:

"It is 50/50 that staying on the drug for two years will produce a weight loss of 16%. Half the people will have less loss than that or will even gain weight. For the average person in this study, a 16% loss was not enough to move them out of the discriminated-against group or make them eligible for a denied surgery. Because half the sample is higher weight than the average person discussed here, assuming normal distribution those people will also continue to be in the "ob*se" category after having a 50/50 chance of losing as much as 16% (for example, a 300-pound person would still have a resulting BMI of 41.9).”

The claims that 77% lost 5% or more (11.5# for the average person), or 61% lost 10% or more (23# for the average person) are not particularly useful for higher weight people in the abstract. Those outcomes need to be assessed for whether they actually reduce harms from stigma and discrimination, especially against the backdrop of the harms of the drug itself, its financial expense, and the weight cycling it causes.

Speaking of weight cycling, they also claim:

Ob*sity is a chronic, relapsing disease that requires continuous effort to control

I would say that this is nonsense, but it’s actually worse than nonsense, because “relapsing ob*sity” actually means “failed weight loss interventions.” This verbiage is an attempt by people who sell failing weight loss interventions to rebrand that failure as “relapsing ob*sity” rather than by its true name, which is “weight cycling.” This also allows them to escape criticism for the serious harm that weight cycling can do.

Their citations for this are another one of the Novo Nordisk-funded Wegovy trials, and a statement from the World Ob*sity Federation which is an astroturf organization (an organization that claims to be an advocacy group for higher-weight people but is, in fact, funded by the weight loss industry.) The WOF takes millions of dollars from Novo Nordisk and other weight loss companies for whom this definition of “relapsing ob*sity” is a priority because they want to sell weight loss products that don’t work to people for their entire lives.

This brings me to another question - one of the mechanisms by which this drug works is simply shutting down hunger signals with some people on the drug reporting that they “just don’t want to eat” or “forget to eat.” Is anyone tracking nutritional/micronutrient deficiencies in those on the drugs or do they not care if people are nourished as long as they are a few pounds thinner and Novo Nordisk is billions richer?

When interpreted together with the findings of the STEP 4 withdrawal trial and STEP 1 off-treatment extension study, which both showed weight regain after semaglutide discontinuation (after 20 weeks’ treatment in STEP 4 and 68 weeks’ treatment in STEP 1) these results support the benefit of continued semaglutide treatment for sustained weight loss.

This is subtly setting up a false dichotomy, as if the only two options are to take the med, lose weight short term, then go off the medication and gain it back, or take the med forever (ignoring that weight loss had, by their own admission, largely plateaued at week 60 while people were still on the drug and that weight was being regained at 2 years when people were still on the drug, when they stopped tracking). Regardless of whether or not they are calling it “long-term,” the follow-up period in this trial is not nearly long enough to make a recommendation to take the drug for life.

Moreover, it should be noted that there is a third option. Understanding, as always, that health is not an obligation, barometer of worthiness, or entirely within our control, there is always the option not to start the medication in the first place, and move to a weight-neutral paradigm with greater health benefits and less risk, but no profit to Novo Nordisk.

Did you find this post helpful? You can subscribe for free to get future posts delivered direct to your inbox, or choose a paid subscription to support the newsletter (and the work that goes into it!) and get special benefits! Click the Subscribe button below for details:

Liked the piece? Share the piece!

More research and resources:

https://haeshealthsheets.com/resources/

*Note on language: I use “fat” as a neutral descriptor as used by the fat activist community, I use “ob*se” and “overw*ight” to acknowledge that these are terms that were created to medicalize and pathologize fat bodies, with roots in racism and specifically anti-Blackness. Please read Sabrina Strings’ Fearing the Black Body – the Racial Origins of Fat Phobia and Da’Shaun Harrison’s Belly of the Beast: The Politics of Anti-Fatness as Anti-Blackness for more on this.

These people/researchers have zero shame. Gross.

So, essentially, this drug works by putting a person into medically-induced anorexia. Since we have plenty of data about the long term effects of anorexia, my hypothesis is that in the next 10-20 years, we’re going to start seeing those same effects from long-term semaglutide use.

I hope this drug is taken off the market.

Can we take a moment to address the death of the one study participant? Did the study attempt to explain this at all? One death out of 152 people should be horrifying, especially for a drug they’re expecting to market to a large population of people. (And not to mention a population of people who have historically received substandard healthcare and may not receive proper interventions before a medically unnecessary drug kills them.)

The drug companies will always try to blame an unrelated issue for study participant deaths (and now they can just blame fatness!), but drug trial deaths should be taken very seriously. Drug trials are a teensy snapshot of a much larger reality, so if this short small study resulted in 1 person dying out of 152 in just two years… RED FLAG. (On top of all the other red flags.)